Annales Monégasques

Historical review of Monaco

Summary

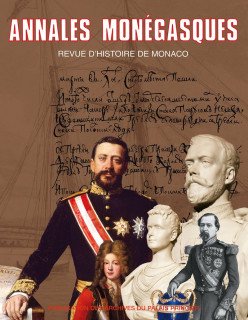

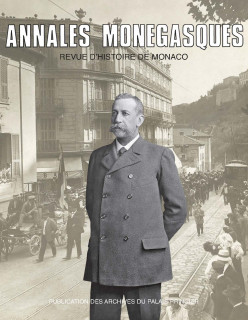

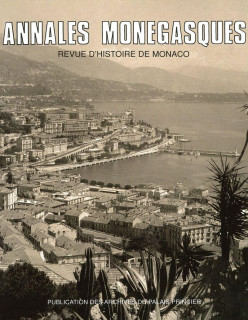

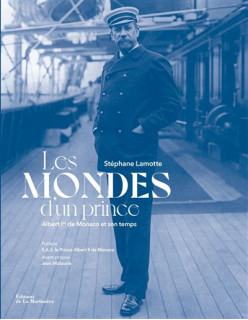

The 2024 edition of the Palace Archives history review focuses on the second part of the proceedings of the interdisciplinary symposium entitled “Careers of a Prince – Lives and Territories of Albert I of Monaco (1848-1922)”, held at the Oceanographic Museum on 24 and 25 September 2022.

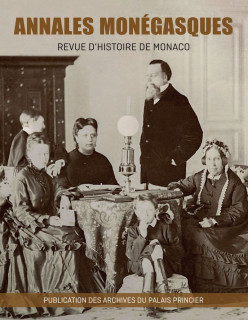

The chapter Learned life and scientific work begins by looking at the close links forged between Albert I and the Académie des sciences over the Prince’s thirty years of oceanographic studies, while his friendship and collaboration with the Portuguese naturalist Francisco Afonso Chaves are explored through the prism of stereoscopic photographs.

The chapter Political ideals and government includes two articles giving an insight into the Prince’s relations with France: a “French” prince, Albert I was a great friend of Monaco’s larger neighbour, and was in frequent contact with the scientific and political communities in Paris and provincial France, whatever government happened to be in power at the time. Yet he also maintained a close relationship with his closest neighbours, the elected representatives and préfets of the Alpes-Maritimes region. On the domestic front, during the Belle Époque period, his reign coincided with a gradual move towards greater political representation for civil society. The Syndicat d’Initiative des Intérêts Généraux (1907-1909) was one of the first institutional experiments in political consultation, preceding the troubles that culminated in the commune being reorganised, and eventually the adoption of a new constitutional law in 1911.

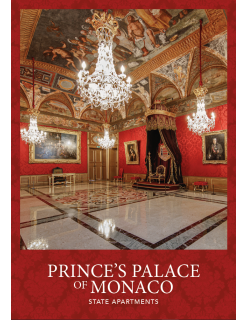

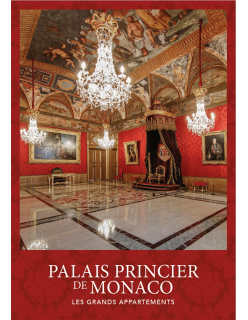

A substantial part of the volume deals with the subject of Images and depictions of power. On his accession, Albert I chose to celebrate tradition, intent that his enthronement ceremony be a grand spectacle to consolidate his position in relation to his subjects. Throughout his reign, his political stances were the subject of satirical caricature and cartoons, often vicious but always highly inventive, with the casino’s scandalous reputation a frequent target. Like his predecessors, however, Albert I sought to promote an institutional image by issuing coins bearing his likeness and commemorative medals marking prestigious events. An honorary member of the Belgian society of numismatics before his accession to the throne, the Prince once again demonstrated his keen interest in the subject in 1910, when he acquired a collection of Green coins depicting marine animals,

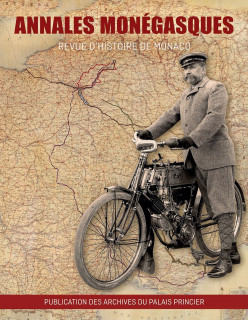

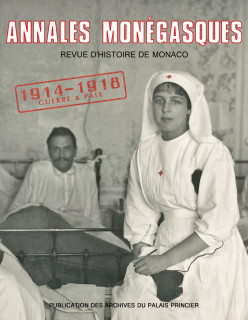

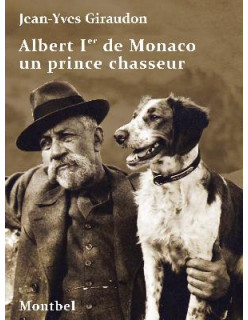

Finally, in the chapter Sports and outdoor life, it is fascinating to recall that, in this year of the Paris Olympics, it was during Albert I’s reign that the Principality joined the International Olympic Committee, with Monegasque athletes making their debut at the Games in 1920.

The bibliographical chronicle continues to highlight the latest national and international publications about the history of the Principality and its dynasty.